Explore your city and its people.

Sign up and experience the pulse of the city and its citizens...

City Pulse

How Tech can build better citizenship

November 05, 2017• By Srikanth Viswanathan

The idea of citizenship is central to a democracy. The meaning of citizenship and what its practice would look like in an open, democratic society is still evolving. Beyond bestowing rights on citizens, what else should governments do to cultivate citizenship? Besides voting in elections and exercising their rights, what else should citizens of a democracy practise in their daily engagement with other citizens and with the state? Discovering practical answers to these questions will be key to strengthening the idea of democracy. The pathway to this discovery does not exist in any finished form, and will need to be created with deliberate and often hotly contested and messy efforts. Cities are most likely to be the places that will witness or even catalyse this discovery.

In 2007, for the first time, more people around the world lived in cities than in villages. By 2050, two thirds of the global population is expected to live in cities. Demographically, economically and environmentally, cities are beginning to rise to global significance on a historically unprecedented scale. Particularly in democracies, the challenge will be to envision cities as economically vibrant, equitable and environmentally sustainable habitats, within a governance framework that builds trust between citizens and city governments.

India’s cities and its democracy

India’s population in its cities is over 400 million, and expected to breach 800 million or 50 per cent of the total population by 2050. The country’s ability to meet the socio-economic aspirations of hundreds of millions of its citizens will depend on how well we manage our cities and their growth. As a democracy, quality of infrastructure and services alone cannot be a barometer of quality of life in our cities. Quality of citizenship is an end in itself, besides arguably being a means to better quality of infrastructure and services. We will therefore need to transform the quality of citizenship in Indian cities at a massive scale to transform quality of life, and through that the lives of hundreds of millions of our citizens.

Civic technology and citizenship

India’s cities are not per se recognised by the constitution as independent units of governance or economy. A constitutional amendment in the early 1990s only walked half the distance and has not been implemented fully by state governments. The result has been a lack of formal platforms and processes for citizen participation in cities.

Technology and social media have however opened up new possibilities. Through its promise of connecting citizens to city governments on a transformative scale and in real time, technology holds out the promise of a two-way communication system, of geo-spatial civic analytics, of hyper-local civic engagement and of data-driven engagement and accountability.

Connecting citizens to governments

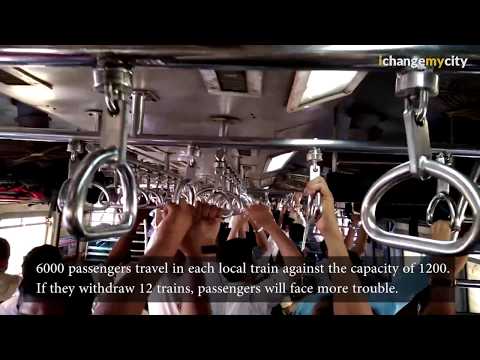

The Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy’s civic technology platforms www.ipaidabribe.com and www.ichangemycity.com have demonstrated that this promise is real.

Launched in 2010, ipaidabribe.com has clocked 15 million visits and was launched in 30 countries. In India, ipaidabribe.com has recorded 140,000 bribe reports across 1,071 cities. We expect ipaidabribe.com to continue to grow in size and impact. ichangemycity.com is a social change platform that seeks to demonstrate a sustainable model for hyper-local civic participation. It now has 500,000 registered users in Bengaluru city.

Deeper penetration of smart phones and falling mobile internet prices combined with the proliferation of easy-to-use mobile applications have further accentuated the power of civic technology. Public Eye, an app for citizens to report easily on traffic violations, was developed by ichangemycity in collaboration with the Bengaluru Traffic Police, a state government agency. Swachhata, an app for citizens to report garbage hotspots, was developed in collaboration with the central government.

Public Eye was launched in 2015 and has received over 90,000 traffic complaints with a 64 per cent resolution rate. Swachhata was built following a request from the Government of India, and is the official mobile application and web platform of the Swachh Bharat Mission across Indian cities. Built under Prime Minister Modi’s flagship mission, the app has witnessed over six million complaints across 1,500 cities since its launch in August 2016. Today, more than 4,000 engineers are trained to use the Swachhata app to resolve complaints in real time – 500,000 garbage dumps have been cleared across hundreds of cities in less than a year.

Both these applications have demonstrated that civic technology can enable large-scale citizen participation in India’s cities.

Some defining features

There are specific defining features of civic technology that are enabling wider citizen participation in India’s cities. Independent civic technology platforms are making two-way communication possible. Government platforms in India are notorious for being black boxes, facilitating only one-way communication from citizens to government without any effective response mechanism. Web and mobile platforms have made real-time two-way communication possible. While the right-to-information legislation opened up government records to public access over a decade ago, civic technology has genuinely democratised this information through wide dissemination in a ready-to-access format and channel. The deepening of civic learning, a stepping stone to citizen participation, is taking root in cities. Civic analytics are powering the leap from open data to actionable insights, where citizens are able to effectively use neighbourhood-level quality of life and budget data to engage with governments on hyper-local civic issues. Such data, when tailored into stakeholder dashboards, is empowering citizens to hold their elected councillors and municipal officials accountable between elections. Geo-locations and realtime communication of photos and videos is further redefining the accountability of civic officials. All of the above features can also be tailored differently for different stakeholders through customised mobile apps for citizens, municipal officials and elected councillors.

Three ingredients for success

Civic technology will be a transformative change agent when accompanied by three ingredients: systematic civic learning, neighbourhood-level community organising, and government adoption. Civic learning is necessary to move citizens through the ladder of citizenship from passive to an interested participant. Neighbourhood-level community organising and civic technology can reinforce each other. While civic technology can enable neighbourhood-level platforms for citizen participation through customised applications, such platforms are necessary to throw the citizenship net wider and engage a larger number of citizens. Government adoption of civic technology is a game-changer, irrespective of whether the government builds its own platform or adopts independent third-party platforms. Government responsiveness is key to sustaining citizen engagement in civic technology platforms. In an increasingly urban democracy with exponential mobile and data penetration, governments are increasingly adopting technology to connect with citizens even if as a signal of political proactiveness.

The future

India’s journey of socio-economic growth will be unique and collaborative. As Swati Ramanathan and Ramesh Ramanathan argued in their recent paper in the Journal of Democracy, India will not have the luxury of evolved state capacities to deliver on human development, but would need to home-grow innovative models of partnership and collaboration. Cities will be at the centre of such innovative models. A multi-stakeholder collaborative model of delivering socio-economic growth at the scale of India’s needs will need an ecosystem of trust. We are weaving this fabric of trust and in the process discovering citizenship in all its colourful dimensions, and deepening democracy in India’s cities, all through civic technology.

This article was first published in Oxford Government Review – October 2017 – Bridging the Gap.

Ò

Ò  Ò

Ò